|

THE FOLLOWING NOTES RELATE TO:JOHN TIDRIDGE AND HIS TIME IN THEGRENADIER GUARDS |

|

THE TIDRIDGE WEBSITE

|

|

|

|

THE FOLLOWING NOTES RELATE TO:JOHN TIDRIDGE AND HIS TIME IN THEGRENADIER GUARDS |

|

|

|

JOHN TIDRIDGE'S FAMILY TREE:

Seven children: John Tythereg/Titheridge (1669-1711), Em Tytheridge (1672-c.90), William Tythereg/Titheridge (1674-1743), Sarah Titheridge (1677-?) Eleven children: They had 7 children: Thirteen children, Tidridges, were: Eight children were: Three children: Four children were

|

|

ARMY In the fifties (1950's that is) every young man in England, was required to spend 18 months in the armed forces: The exception being if he were still in school or an apprentice, or was in a special job. This meant joining either the Army or the Air Force. The Navy was fussier and would not take men on National Service, the name given the period of service. This presented no real problems for me, apart from natural apprehension; it was just another phase of life that one had to go through. That sounds really corny, but people never seemed to make such a fuss of the 'phases of life' or whatever, as they do now. We never had the time to discover ourselves. Back in the old days, you were born, went to school, went to work, did your time, (National Service!) got married, retired and then died. Life was less complicated. Shortly before my eighteenth birthday I received my call up papers telling me I had to go to an office in Southampton. I'm not sure which came first, but there was a Medical and an interview with a sergeant. Because of the interview, I decided to join the Grenadier Guards. I signed on for 22 years, with the option to leave as each third year occurred. So, at 18, I had a career. The medical came next, lines of young men standing around in their birthday suits, coughing in all the right places. The result was, I passed the medical with 'flying colours', fit to serve in the furthest flung corners of the Empire, doncha know! The doctor found, and marked on my medical card, that he found flea bites on my shoulders. My Mum, no, she didn't come with me for the medical (!) however, she was horrified when I told her. You have to know that having fleas was a sign of uncleanliness and gave all those bad impressions Mum was so worried about. The doctor found no fleas. It would not have been surprising if he had, as I worked on a market garden where there were animals. All the animals were carriers of fleas. |

CATERHAM BARRACKS

It seems that after the medical and the actual 'signing on' there was a delay before I got my marching orders. Eventually the orders arrived and I was to report to the Guards Training Depot,Caterham, Surrey. While for you guys a 100-mile trip is peanuts, to me, it was my first real journey away from home. Further, I had no idea how to get to the place. It meant changing trains a couple of times, culminating in a bus ride. I distinctly recall receiving many looks of sympathy when I asked for Caterham Barracks, the Training Depot for guardsmen.

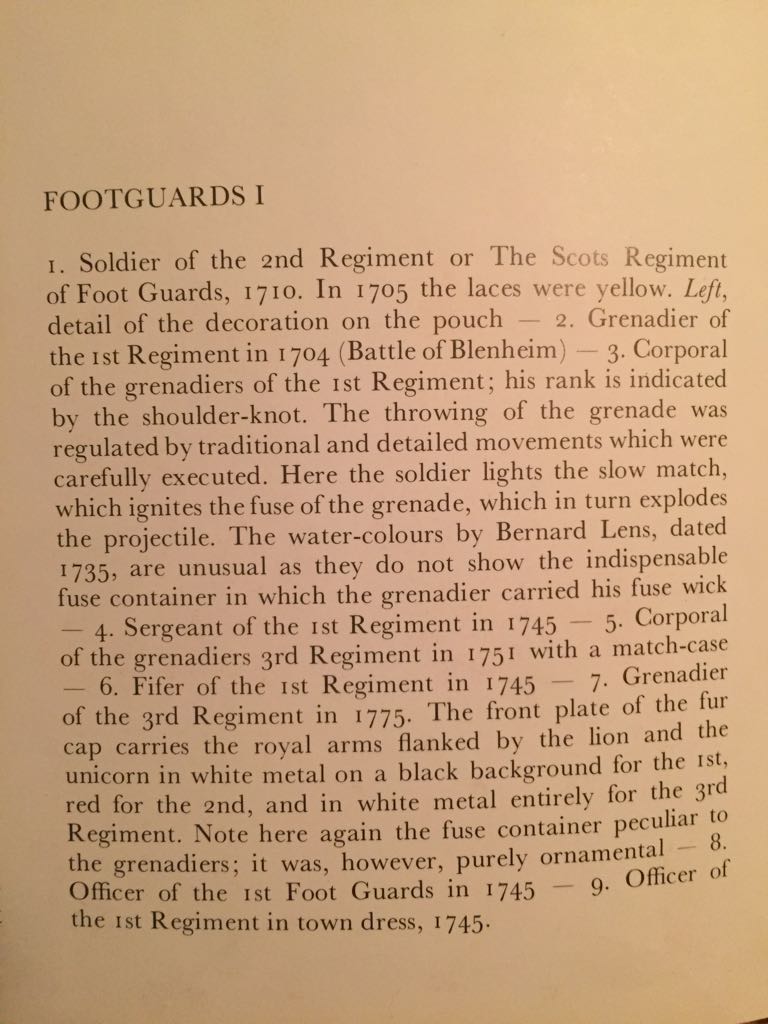

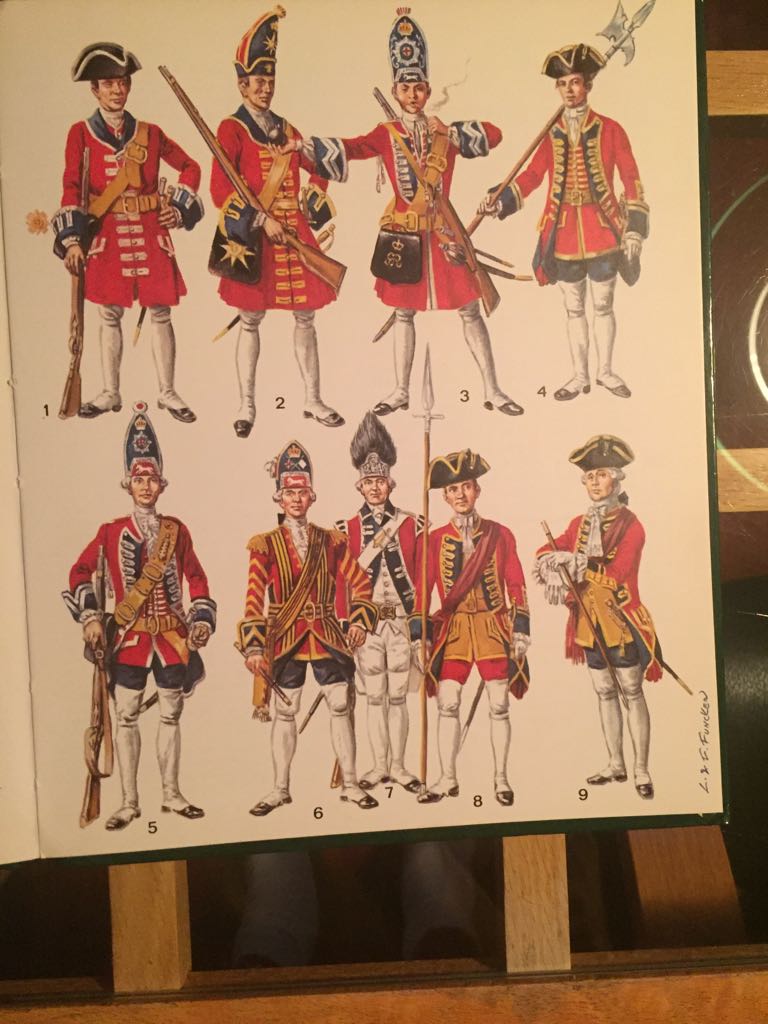

I should depart from this discourse at this point to tell you something about the Grenadier Guards. It was, and still is, recognized world wide, as a fine regiment. The training is one of the toughest in the world. They say, and it is true, once a Grenadier ALWAYS a Grenadier. The Regiment was formed in 1656, and since then has won many battle honours and awards. Don't let the Americans convince you they did it all. They just blow their trumpets louder. The Regiment, along with others of the Household Brigade are, during peacetime, responsible for Guard duty at many of the tourist attractions in London. This includes Buckingham Palace, Tower of London, St. James' Palace, and I believe, still, at night, the Bank of England. In wartime they are usually shipped to the trouble spots. They have served more recently in the Suez, Northern Ireland, Falkland Islands and the Gulf, Afghanistan and Iraq.

Now back to my story: On arrival at the gate I approached a sergeant, (this much I knew about the army) he was a fellow from good old Totton.

I was trying to recall some highlights of my stay at the Depot. The one that comes quickly to mind was the coronation of Elizabeth II. We were given the day off, the Colonel of the Regiment, a very distinguished elderly gentleman visited us, had dinner with us. We received five Woodbines, very cheap and nasty cigarettes and a glass of warm beer. We watched the service on television screen (TV), on a huge screen. This was the first time I had ever seen TV. I was eighteen years old. There was another day off, for Grenadiers Days, and we had the day to ourselves. I believe we actually saw the inside of the NAAFI, the canteen. Saturday was supposed to be a half a day off. It turned out that after drill you had lunch and then were paraded for fatigues, i.e. extra duties.

Sometimes you were lucky and received a job that took but a couple of hours, sometimes, and depending on the non commissioned officer that supervised, it could last for the rest of the day: Sunday. A couple of us learned if you went to church , you received a late breakfast and this meant double helpings. You also missed the fatigue parade, so you had the rest of the day to clean kit or just lay around. Not a very good reason for attending church.

The most dreaded chore was to work in the cook house. Not only because it was usually all day but also because it was the cook house, with greasy pots to wash and spuds to peel. You did, however, get extra portions of food. Unfortunately, after working in the cook house all day the last thing you wanted was food: Especially army food. I remember being assigned to the cook house and being told to fill a huge copper boiler with vegetables for stew, about a third of the copper was full of custard. The sergeant who simply poured the new ingredients in with the custard quickly resolved the problem of removing the custard. Strange but true.

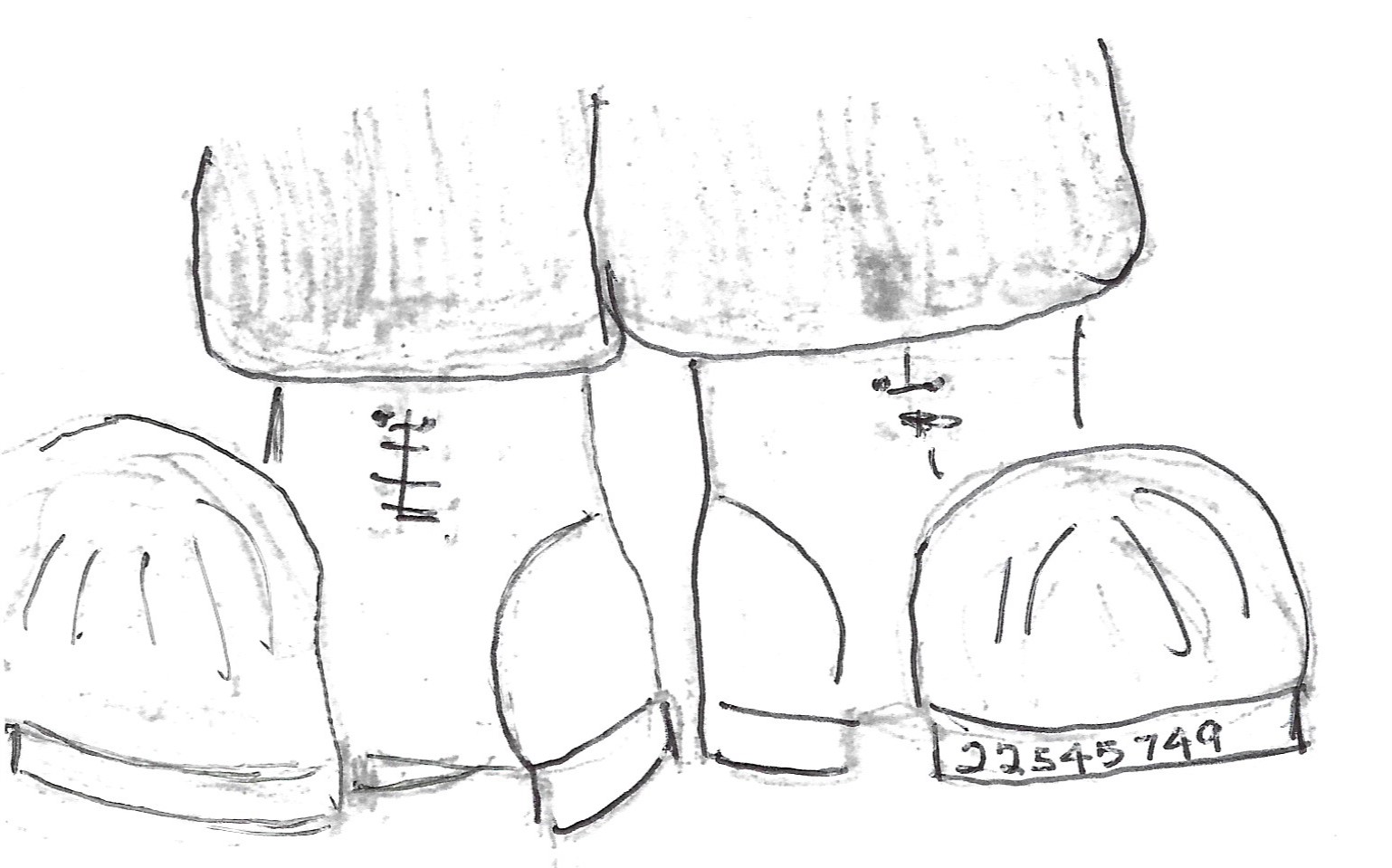

We also received lectures on not cavorting with strange women; they probably include strange men as well now, and all the terrible things that could happen to you, if you wandered from the straight and narrow. The lecture was given by a senior non-commissioned officer, and, at least he seemed sincere. I would guess the armed forces had its share of venereal diseases (VD) and other problems. Another joy was 'Kit inspection' . This exercise entailed setting out your kit on a bed in a particular order. The kit had to be squared off, with your regimental number displayed on each item. My number was 22545749. Standing at the side of the bed you awaited the inspecting officer.

A shirt held by the shoulder lapels in each hand and, over the other arm, a pair of socks, your hands up and touching your chest, and with your feet apart. When the officer approached you brought your feet together and said something like this, and, at the same time holding out the shirt, turning it around for the officer to see then throwing it over the arm that didn't have the socks and at the same time extending the arm with the sock so that the officer could see them, '22545749 Recruit Guardsman Tidridge J, washing at the wash'. This would account for some items not being displayed. You can appreciate every item of army equipment you owned was displayed and laid out on the bed.

In the early stages it was a pain to have to do this. On one occasion the Officer left, the sergeant remained behind and told us to face our beds: Then, to grab the edge of our beds and to tip them up. Apparently the inspection had not gone according to plan. Ah, the joys of army life.

It seemed that everyone in the squad was charged with one or two minor violations. Presumably this exposed you to Army discipline. I was charged twice, the first time for dirty flesh. During an inspection, where I had my rifle over my shoulder, at the slope, four fingers of my left hand were visible, along with my thumb. Let me first explain the system: When you are on parade and the officer approaches you, you have to yell out your name. Then the inspection begins. The officer noticed some polish on one of the fingers. Now, the Officer didn't say, "dirty flesh" he merely pointed it out to the Senior Non Commissioned officer following him: He then yelled, "Guardsman Tidridge, dirty flesh Sir", acknowledging the officer's remarks. Then your own Sergeant, who would be bringing up the rear, would also yell out your name and the offence. Seemingly, each person added volume to the yell. Fortunately there were usually only a couple of yells.

If (and it never happened to me) the officer found two things wrong, then they would be yelled out, and it was then a sign for the Senior Non Commissioned officer to have a look as well. If he found something, the next yell would be, and you must remember that some times there would be over 200 men on parade, and generally when the yelling started everyone listened for the next phrase which would be, "Piquet Sergeant", and, a sergeant on special duty, waiting on the edge of the parade ground would suddenly appear by the poor guardsman. He would hand his rifle to someone, the command would then be, "Put this man in close arrest", and the poor fellow was marched off to spend the next little while cooling his heels in the guardroom. Later, he would be marched in front of an officer to receive 'his just reward', usually in the form of extra duties of some kind.

The second time I was charged, it was along with several others. We had been practising, standing at ease, this meant moving from a position with your feet together to one requiring you to bring up your right foot about 12" and then slamming it into the ground so that it finished up 12" away from the left. Apparently we had moved our feet less than the required distance, and we were charged with `being idle on parade'

Being charged meant having to be marched in on Company Commander's Memorandum. On both occasions we (the accused) were marched in as a group. The charges were read out, we were asked if we had anything to say, we didn't. We were given a stern lecture and then marched out again. While I did not have to appear often, I did several times, and always for minor offences. On one occasion I was charged for having dirty greatcoat buttons. This was much later, in Berlin. The coat was hung on my locker and was inspected as part of the room inspection. In my own mind there was only one dirty button, not the other dozen or so that were on the coat, these were clean. After I had been marched in and the charge was read, the officer asked me if I had anything to say. I responded in the only acceptable way, "I thank you Sir for leave to speak". This was followed by an immediate, "Shut up", from the sergeant who had charged me, also standard practise.

The officer, however, let me speak, and I won. The sergeant didn't hold it against me. During the thirteen weeks I also earned my Army third class certificate of education, which taught me among other things to read a map... funneee!!! At the end of thirteen weeks we graduated, and, I don't remember for sure but I think we had some leave.

He chose not to recognize me. I quickly learned that trainee guardsman did not really exist, except to be shouted at and 'driven', not in a vehicle, I can assure you, but by everyone else who took it into their minds to. He managed to give the impression that he was looking down at me, even though he was only about 5' 11". He shouted, "Piquet" and a body, dressed in uniform, appeared from what I later was to learn was, the guardroom. He obviously knew where to go. I was given instructions to follow him so took off after him, travelling at a pace I was not yet used to, though I was never a slouch.

I forget much about the first several days. There was a long episode of filling in forms and generally being yelled at. Utter confusion. At some point in time there was an aptitude test. I remained a guardsman, so obviously I had made the right choice. Ah, well, that's life. A hair cut, one of many I was to endure in the next several weeks, was fitted in somewhere in the hurly burly. It seems to me there were five barbers, same number of chairs, and twenty-five or so of us. Fifteen minutes later all of our hair had been cut. Real punk, but no safety pins. I remember one lad crying as they cut off his wavy hair. What was under the hat was yours, what was outside was the army's. The barbers assumed our hats would just sit on the tops of our heads.

We were billeted in a large hut for about three days, while they, the Army, we later learned, was securing enough `victims' to form a squad. I always remember my Mum telling me that guardsmen were gentlemen's sons. This illusion was shattered at the first meal. It was absolute bedlam, survival of the fittest. If you sat in the wrong spot on the table you didn't get any bread. You quickly learned! What I discovered later was that it was the officers who were the gentlemen's sons! Needless to say they didn't eat with the unwashed. The life of leisure did not last long. We were assigned to a squad, and a barrack room that would be our home until we graduated from the Depot. There were about 20 of us. Some were regulars like me; others were common National Servicemen whom we looked on with some unwarranted disdain. We were all in the some boat and we would sink and/or swim together.

Most of us were 18 to 19 years old, although a couple were quite ancient at 26 years of age: Mostly from a working class background. If I only tell you half of the things we went through you will all wonder why we put up with it. Quite simply, we were prisoners of the system. Literally, whom would you complain to? All people at the Depot, apart from your group, were part of the system: a system that had been in place for probably a hundred years. It was a system, which worked to mould green (light and dark!!) recruits into a cohesive, military unit. It worked before, it worked then, and it still works now.

In spite of the dumb things we had to do and had done to us, there actually did come a day in the life of the squad when you knew you had arrived. At that point everything fell into place, and junior squads accepted you as a guardsman and; although you had not yet completed the training. The instructors knew that you had made it, because they had helped you arrive and they felt some pride in a job well done. It arrived in week 8 of the 12-week training period. There was not too much room for individualism, though you were expected to be self-reliant. You ate, slept and drank as a squad. You suffered as a squad, you rejoiced as squad. (Sounds like church... but I can assure you that was where the similarity ended)

You learned very quickly you had to stick together. Those who didn't fit in were removed, sounds terrible, but one day they were there, the next day they had left. We had one fellow try suicide, not very successfully; they found him standing in front of a mirror, dragging his razor across his throat. It was enough to get him transferred to another unit. Another was transferred because he never did learn his left foot from his right. He appeared to have been a card short of a deck. I think he was sent, 'in disgrace', to learn to drive a truck. In retrospect, we marched everywhere, he would have driven. I'm not sure who was the craziest. I mentioned, we were now in our assigned barrack room.

Trained Soldier Ron Dancer

The room was one of several in which trained soldiers reigned. A Trained Soldier was a trained guardsman, but he certainly could have been the Deity or someone from a warmer clime. He, however, controlled our destiny, night and day, for the next 12 weeks. You did not even move without asking him. He was the original!!@$#%& He was well over 6'4", probably 220 lbs plus, and, as Jim Crouche would have said, "meaner than a junk yard dog" (and then some). In another country he would have qualified for the Gestapo. Or at least we thought he could and probably was, only with an English accent. If you don't believe me, take a look at him in the photo, he's DANCER, and I can assure you, no Fred Astaire. Looking back almost 40 years later, it is easier to appreciate his position, and to understand to some extent, his attitude. He was responsible for teaching us recruits to survive.

He taught us how to spit and polish boots (officially the polish was forced into the boots to fill in the cracks and pimples, and solidified with spittle) but everyone knew the leather was smoothed down with a hot iron or spoon, and then shoe polish was added in quantity to the smooth surface along with the essential ingredient, spit. This, with the addition of elbow grease, lightly applied, did indeed, create a sparkling surface. It was mandatory that you could see your face in the shine. He was responsible for us learning all the strange things associated with barrack room behaviour: How to lay out a kit inspection (all the equipment, clothes issued by the army). And, they did issue everything, right down to dark green under drawers, possibly stolen from the French at the Battle of Waterloo! He taught us how to lay out lockers for inspection, how to make up your bed. If we screwed up too badly, he got the blame.

Let me quickly list some of the things we did. If you wanted to leave the room you had to go to the door, bang your feet in a drill movement, and say, " Leave to fall out, (i.e. leave the room), Trained soldier." Simple enough, however, if Dancer was in a bad mood you might have to do this several times, before he would even acknowledge your presence. You could then get remarks like, "are your feet sore, I can't hear you?", indicating you had not stamped your feet loud enough; or, sometimes a straight 'NO'. The next poor slob would do it exactly right, based on Dancer's remarks about apparent lack of sound, only to be told "I'm not @#%& deaf, try it again". If you had running shoes (plimsoles) on, your movement was not loud enough, if you were wearing boots, too loud. You had to go through this rigmarole every time you left or entered the room. He 'shared' in your food parcels, and let me tell you, two things were evident in your life.

You were always tired, and always hungry. Not necessarily because you were underfed, or did not get the required amount of sleep, but you were always on the go during the day. You were always moving at a very quick rate of speed, arms swinging, and, as they constantly yelled at you, "dig your heels in". He 'allowed' one of the fellows go to the canteen to get snacks, if we collected enough to give him some. He was an aggressive person; it was not unusual for him to physical encourage recruits if they flubbed up on some small thing they were required to do. There was no recourse; you couldn't even show a retaliatory response. Or at least we didn't; having said that, I really don't bear him any grudges. I didn't like his style, but he was respected throughout the Depot, as one of the best. This was of course, not based on how he got the good results he did, but on the good results.

Let me run (and sometimes we did) through a day. Wake up was at 6.30 a.m. but we were always up long before that. There was washing and shaving, always with cold water, to be done. The cold water was not punishment; I really think the place was so old there just was not any hot water. The only time we experienced actual hot water was in the weekly shower. That in itself was an unforgettable experience. The words of command were, "Get undressed, get in the shower, get out of the shower" Expletives all deleted. And it seemed like the amount of time allowed was about as much as it has taken me to type this portion, i.e. the words of command!! Why up so early you say, there would not have been enough time to do what we had to do before we were scheduled to go on parade!! First a fair hike to breakfast and back: The last minute cleaning of boots, badges and belts, and, for heavens sake, the setting up of the room. The room had to be set up just so.

Let me explain, if I can remember. By now, the equipment in the form of belt, ammunition pouches, haversack and backpack had all been issued. It had to be blancoed, blanco was a green substance applied wet to the outside of the equipment, which presumably preserved it, but was also camouflage. The equipment, minus the belt, had to be squared off with cardboard and had to be set out just so above your bed. Each piece had several brass attachments. The brass had to be cleaned everyday.

Somewhere on the large haversack you hung your nameplate , made of brass and had to be shined everyday. Along side of the bed was a locker; this was left open during the day for inspection. Every item in the locker was on display. Knife, fork and spoon, eating for the purpose of, mug, enamel, drinking, for the purpose of: A housewife, which was not a French maid, but a small satchel in which was a needle and thread, wool, and thimble. And one of those wooden toadstools you put in a sock when you darn it. In the bottom portion were your best boots, shined. To one side was your rifle, somewhere else your great coat, properly folded and all the buttons shined.

Every morning beds had to be made as follows: The mattress was folded in half, and the crease side placed at the end of the bed. One blanket was folded to be a wrap around. The sheets and other blankets were folded and then, wrapped around with the first blanket you had set aside. The sheets and blankets were in order so you finished up with a product looking like a layered cake. Again, everything was supposed to be square and straight, and, well you get the picture. I know you are probably saying what was the point? Think about it. It was one way of ensuring the beds were aired, and perhaps, discovering those that may have need medical attention for problems that had not come to light earlier. Then, and I don't believe this myself; the beds on either side of the room were lined up in two rows. They remained in the same location, but the ends of the beds were actually lined up by stretching a piece of string from one end of the room to the other.

Each pile of blankets was also lined up. Beside your bed was a kit bag, which if you were moving anywhere would be full of clothes. It was about 9" in diameter and 3' long. The material was quite stiff, which was just as well, because you had to stand the kit bag up, empty, and line them all up. Then the handle, which was of rope had to be twisted to stand up, straight! The dumb part about this whole exercise was that in time you actually enjoyed doing it, and, in effect, in your own mind, defeating the system by doing these ridiculous things, well. However, in actuality losing, because not only were you doing what the system wanted, but you were actually enjoying it!!

The photo to the left is from a book called:"The Guards and Caterham. It was taken in the 1920's but the barrack room was the same, only the beds were full size in my time.

The first sergeant we had was a 'gentleman', and I suppose, based on the results of our first pass out inspection, four weeks later, we undoubtedly took advantage of him, although, unbeknownst to us, it was to our detriment. You have to understand that a Trained Soldier, although actually only a guardsman, was, at the Depot, a person of authority. As recruits we had to stand to attention when we spoke to him. A (lance) corporal, wearing two stripes was even higher, and the (lance) sergeant, who had three stripes, was thought to be able to walk on water.

Let me insert a little of Brigade of Guards history here. In all other army units within the British Commonwealth a lance corporal wore one stripe, as did lance corporals in the Brigade of Guards, way back, even before my time. Apparently Queen Victoria saw a guards (man) being posted, not mailed, but taking his position at his post. This was not a wooden stake, but the position he would remain at for the next two hours , by a lance corporal, with one stripe. She was not amused by the one stripe he wore to signify his position, and ordered that in the Brigade of Guards; lance corporals were to wear two stripes, Corporals three. Next there was a colour sergeant, who wore three stripes and a crown and so on and so on. Those of higher rank, very seldom acknowledged our existence, unless it was to administer some kind of discipline.

Where was I, what has the above to do with the downfall of the sergeant. Basically it was because he found it hard to accept the required, strict separation between recruits and non commissioned officers. He would visit the barrack room in the evening and chat with us. Somehow we must have picked up that he was not tough enough. Consequently we did not learn our drill procedures as we should have done. We flunked our fourth week inspection. Had we passed we would have been entitled to our first weekend pass. Quite a disappointment: In addition, the sergeant [Sgt. Searcy] was returned to the battalion, in disgrace. We were to pay the piper for the sergeant's downfall.

L/Sgt George 'Bunny' Whitehead

Sgt Whitehead remained in the Grenadier Guards retiring as a Lt. Col. A job well done. Died November 2022.The next sergeant we had, and I might add the last one, was a sergeant Whitehead. Dancer, in comparison, was a wimp. Whitehead was only about 6' 3", not as heavy as Dancer, but mean, again, look at his picture. You will know the meaning of esprit de corps. This came into play as soon as Whitehead took over. It appeared that everyone who had any authority of any kind was going to get in the blows against this squad that had done so miserably, and had their sergeant back in disgrace to his battalion. The fact that basically it was his fault had no bearing on the issue at all. As the expression went, 'our feet never touched the ground' for the next several weeks. We certainly paid the price for the sergeant's failing, as it implied he couldn't cut the mustard with a training squad. By never allowing our feet to touch the ground meant that we were doubled everywhere, continually yelled at.

Any free time was cut to a minimum. Any sign of slacking off meant an immediate journey to the drill sheds where we were (illegally) marched to the beat of a drum. Let me tell you that could be very fast.

Each morning started with a drill parade, but more about that later. You would have dinner, it was a little more relaxed after lunch; at least you could stay on your beds now that the room had been inspected. We made extra?ordinary use of our beds; they were our beds, tables and chairs. There was no other furniture in the room apart from the beds and lockers, and a table for ironing uniforms on which we were not supposed to do, and didn't incidentally, the Trained Soldier did though. The mid morning parade, gave those who had the privilege of doing it, time to inspect the barrack rooms. By the way, we were in a barrack block that housed several squads of men. One quickly determined whether the room had passed inspection. If the room was not up to standard, you could expect to find your bedding in a heap on the floor. Contents of lockers thrown all over and boots dumped in the water in the fire buckets.

Like I said, it was quite the system, but who was to argue?

More military stuff in the afternoon. In the evenings a jolly time was had by all. It was equipment-cleaning time. And of course, equipment was never clean/shiny enough for Dancer. It could cause you, if you didn't reach the required standard to spend time in the washroom, after lights out, which was also illegal. Checks by senior sergeants did not occur often, probably just often enough to say checks were made on a regular basis to fulfill some regulation ensuring soldiers were not required to stay up beyond lights out without good cause. I doubt if any member of the squad failed at one time or another to burn the midnight oil in the washroom. Needless to say your instructions, which you had to deny you had received, were to say that you just wanted to look better and that you chose to spent time in the washroom. Back to the equipment cleaning: You used your bed as a bench, except for any water assisted cleaning of the belt and pouches.

You sat for a fixed period of time. Ninety minutes comes to mind, straddling the bed, with suspenders down. Goodness knows why. While cleaning, you were expected to listen to, and become familiar with, the bugle calls that were sent across the Public Address system. There is a bugle call for everything in the army. Well almost everything. The bugle calls, played by a drummer, included calls to get up, go to bed, pay parade, alarms, ad nauseam. In addition we were expected to learn and remember all the battle honours of the regiment. There were around fifty when I was in. The sergeant would occasionally visit, and normally, at least with Whitehead, they were not social calls until we were well on our way to graduating. Again, no trips to the canteen, except for one person, who took a long list for the squad, and one for the Trained soldier, who had to be fed.

At ten o'clock, 22.00 hours, the cry, "Stand by your Beds" was heard and you had to stand on the end of your bed, pants rolled up to the knees, suspenders dangling. The picket, occasionally spelled piquet, sergeant who was the duty non commissioned officer for the period, arrived shortly thereafter and determined that everyone was in, there was really nowhere to go, unless you were sick, or absent without leave Generally speaking, at this time of night they were much more human, and would joke around a bit, just to let you know there was an end to the training. As you progressed in your training so the strict regulations were relaxed, just a little. Please don't the impression it was terrible all the time. What the training did was to get you to share with others, and develop a philosophy covered, in Canada, by the letters, d l t b g y d !!! You have to remember that it was the squad that graduated, not a group of individuals.

It meant that those who picked up the system quickly helped others. Of course, some of the methods would make your hair (I had some then) stand on end. Depending on the circumstances, help was either pleasant or unpleasant. If it came to cleaning equipment those that could do it better helped out the others. The Trained Soldier helped as well. Remember you graduated as a squad, so it required all the squad to pass the inspection.

However, there was the Obstacle Course. This would be a lay out in a field with walls and barriers and water and things like that. Every squad had one or two men that couldn't swing like Tarzan and would let go of the rope too soon and fall in the very slimy water. Or, unable to climb the wall or jump down from a six foot log fence. This, in the view of the system and the other squad members, showed an individual weakness that had to be corrected. It could mean the difference between survival and whatever, and it had to be an individual effort. Those who could were always able to complete the course sat down and waited for the inevitable. Not recommended these 'politically correct' days and it didn't really help in those days either.

You shared food parcels with the fellow next to you and with the Trained Soldier if he heard the rattle of paper after lights out. Our Trained Soldier, in retrospect was not very smart, he had one of the guys write his letters to his girl friend, but he did try. He would take the odd weekend off. He would broach the subject by saying.. "I have the opportunity to go home for the weekend but I'm broke, if have to stay here then your lives will be as miserable as all get out", that was the general drift of the message. A passing around of a hat always resulted in enough 'gifts'. Soliciting funds would have been illegal. We didn't begrudge it and we only received a pittance for a salary.

I remember on one occasion he explained he was going out to tie one on, get drunk, we decided we would get a measure of revenge. I don't recall it as being malicious in any way; after all, Dancer had most of the answers to the questions for us to get out of the Depot. We simply made an obstacle course from the door to his bed, which was in the far corner of the room, with kit bags. He made the bed, with some difficulty, and took it all in good sport.

As I said earlier we failed our first pass out parade, miserably, and everyone seemed to know about it, the instructors, the other squads. You really suffered. However, after a week of Whitehead we tried again and made it. All seemed to be forgiven. We had now been prisoners of the system for almost six weeks. We were anxious to get home. The system, however, had not done with us. We got dressed and as a squad were marched to the guardroom to be inspected to see if we were good enough to get out of the barracks. It was about a mile, or so it still seems, to the guardroom. We were marched to the guardroom, almost, turned around and marched back again almost to the barrack block. I swear we did this at least 6 times. Finally we were stopped at the guardroom and inspected by the sergeant who sent every one of us back to the barrack room because our shoes were dusty.

I kid you not, I know, I hear you all saying they wouldn't do that to me... wanna bet!!!

While I remember, a couple of things stand out in my memory, the first, shortly after we were settled in as a squad, the question was posed, "how many of you are confirmed" (in the Church of England). Those that were not were sent on the appropriate course and in time were confirmed. I had been. It had nothing to do with Christianity. It was just something that they army was `concerned' about. The second of the things was not really related but when you had time to think, which was infrequently, you knew just how hungry you were and just how tired you were. You ate anything and everything you could lay your hands on.

Army food, as I recall, was barely one step above pig swill, and the cooks, who must have shuddered if they had actually been taught to prepare meals, seemed to ruin everything they tried. I have eaten roast, boiled, and stewed corned beef. If BBQ's had been available we would have had that as well. As for the tiredness, if you received class instruction you were always in danger of falling asleep. And it was dangerous, if you were caught, you finished up in the clink.

You learned several Grenadier traditions, which will mean absolutely nothing to you but which I am going to tell you about anyway. Everyday at 16:30 hr., and usually as you made your made your way to eat; the drummer (bugler) would sound `retreat'. Now, Grenadiers do not know the word retreat, so, while everyone else around you marched on, you stood still. You never said, "Yes" either, goodness only knows why, so if the Sgt said, Tidridge you are a dumb cluck, right? It would be wise to answer, smartly and sharply, "Sergeant": Which was always pronounced as Saaarnttt!!!! (It was never wise to argue with a sergeant). Just one more and then I am finished. In drilling with a rifle there were several orders that included the word Arms i.e. rifle, however, Grenadiers did not say the word, "arms", so it was anything, more or less, that followed the direction, such as slope.....

The physical training was fairly intense, not very imaginative. There was no slacking off but at least most fellows could run and jump and keep in time with the fellows in front. If you couldn't you could always hang on the wall bars until you thought you could. I think the `drills' they did were dreamed up long before my time and I doubt very much if they have changed. When I joined the Police Service we did the same kind of things. I thoroughly enjoyed physical training, P.T. as we used to call it. You might think that as we were going to P.T. we would change completely ready for it. However, that was not the case; you were in vests, shorts, socks and regular marching boots. Your running shoes were wrapped up inside of your towel. If it rained or was cold you wore the same stuff, but wore a greatcoat as well. [February 11, 2018: I have a note from Sgt. Potter's wife, and as I read it and this earlier entry I realized I had not mentioned the good sergeant's name! And of course I would not have known his first name...Oh woe is me! I replied to Trudy and asked for a new photograph].

Received your account this morning from my son to tell me there were pictures of my late husband L/Sergeant John Potter I was the third wife so some distance from those days but heard many stories. He left the Grenadiers in ’55 having served in 3rd then Kings Comp. then returned to 3rd before 1st returned to UK from Libya just before the King died.He then served in the canal zone. He died in Ireland aged 72 February ’05. Trudy Healey-Potter PS he wrote his biography

Then, of course, there was the floor, made of hardwood, which had to be shined every day. You had your own bed space to do, plus a portion of the floor. The floor was shined with steel wool, and buffed with a blanket. It required the cooperation of everybody, the `skivers' , those who sluffed off, were quickly determined and they were made to do their share. All the responsibility for teaching us these earthshaking duties fell on the Trained Soldier's shoulders, and large as they were, it sometimes, I think, laid heavily. The Trained Soldier survived 13 weeks with us. I don't suppose he was any more pleased to see us leave than we were to leave him.

February 11, 2018

Hello Trudy,

Thank you for your note....[you may have already received this but I had a minor senior's moment!]

Sgt. Potter was a good PT Instructor... trained us hard and well. I have absolutely no negative memories of him at all...

I have put your email on my web page...hope you don't mind! Is his autobiography on the web? Do you have a copy?

John Tidridge

Coming back after the first 48-hour pass brings back no negative thoughts.

When we started training and were marching, we had to swing our arms up shoulder high: Which is OK as long as you are not moving too swiftly. At some point in time, and you had to earn the honour, you were allowed to swing your arms waist high. That, of course, marked your squad as having achieved something. Let me tell you every little credit earned was earned and appreciated. Somewhere along the line we also began to use rifles, (Lee Enfield 303) not only for marching with but for firing as well. One learned it was almost a fatal mistake to call a rifle a gun. The serial number was quickly learned as very often you had to place your rifle among many others. At first the rifle seemed heavy and we were awkward handling it.

Exercises had been developed for strengthening the wrists and arms and pretty soon you were tossing them around without any problem at all. One never handed a person his rifle, it was thrown, properly, so that he could catch it. The wooden part of the rifle had to be polished. This meant, over a period of time, building up a layer of polish on the rifle so that it could be spit and polished. This was a messy job and you can imagine that the shine did not last long once you starting drilling with it. You can perhaps imagine too that there were several exercises that could be turned into punishment with the rifle, the best (worst) was to have to hold the rifle out at arms length, or to march with the rifle above your head, all very jolly, but I suppose it served the purpose.

Don't get me wrong, very few of us were perfect and some days nothing went right. The squad just didn't jell as it should and a couple of chases sure got you limbered up quickly. 'Warming up' they call it in the athletic world.

PIRBRIGHT

Surrey, UK.After the Caterham experience we reported to Pirbright, for Field training. Life was much more relaxed; they were more interested in making you able to defend your country rather than to march around it, although you had to be fit. The food at Pirbright was better and in larger portions. Which reminds me, at each meal an officer visited, he was the duty officer, and a sergeant, the duty sergeant, accompanied him. The men were asked if the food was alright (compared to what) there were seldom any complaints.

We were always so hungry we always ate what we were given. At Pirbright we learned more about different types of weapons, including the Bren and Sten guns, hand grenades. We were shot at, just kidding.

They sat us up on a hill and sergeants took shots from a distance toward us so we would know what a shot sounded like. It seemed we did a lot of marching, and then lot of exercises so that we could know how to charge and stick bayonets in the enemy.

We were taught to yell when we charged. To me it seemed rather uncivilized and one needed to take a more definitive, thoughtful approach. After all, it seems unlikely the fellow, in real action, would just stand there and let you run 8 inches of steel through him, however, yell you did!!

When we did march we were given the opportunity to sing or double. Usually, before you could think of a song the sergeant made you double and then when you were slowed down you were too out of breath to sing, so you doubled again. Great sport. The intent was the same, to make you fit and able to carry on. The good thing was that generally, the sergeants had to run with you. You quickly remembered all the slow songs when you did sing, like `High Noon'

We were exposed to such things as tear gas. Sent through a tunnel, which seemed to be very long and it was only about three feet high so you had to crawl through it. It had water in the bottom. While this may seem OK you we also had equipment on and carrying a rifle. We also had to crawl under barbed wire and do all the things you see them doing in war movies. It was, however, all great fun and I would not have missed it for the world. Somewhere in the middle of the six weeks we all went off to Yorkshire, a place called Pickering.

PICKERING

Yorkshire, UKAgain all kinds of good training including several days in the field: attacking an imaginary enemy, capturing prisoners and getting a chance to swing at the sergeant if he was in the attacking force. Much more to my liking. As I recall the food was fantastic. It was in Pickering that I first saw margarine applied with a brush. I'll hasten to explain. Each morning as we left for exercise we received a couple of sandwiches, you grabbed a couple of slices of bread, and the cook painted it with margarine, and slapped corned beef between the slices, luverly!! I would guess someone had discovered if you warmed up the margarine it could be applied more easily than spreading it with a knife. The period in Yorkshire was finished by a 22-mile route march, which we all finished. 22 miles is not really that far when you are young. However, we had been out on an exercise, and had been without sleep for a minimum of 24 hours. That was part of the test.

I nearly got into deep trouble in Pickering. One evening a mate and I, 'walked out'. We went out to the local village and innocently bought some fish and chips and began to walk down the street, in uniform, eating them. From out of nowhere a sergeant appeared, chewed us out really good. He also threatened to lock us up for disgracing the regiment, and etc ad nauseam. He finally told us to dump the fish and chips in a nearby garbage container and to be thankful he did not have the time to take us back to the barracks and lock us up.

We returned to Pirbright and finished our training, this too finished in a route march that had to be accomplished in a certain time period that we accomplished. We had now completely vindicated ourselves. Looking back on the training it was tough but I think most of us enjoyed it!! I don't think there was another way to mould an untrained bunch of kids into a fit, well-drilled and trained squad.

I have pondered quite seriously the training methods and I really don't think there is another way.

|

LONDON AND THE BATTALION The squad was then split up to report to one of the three battalions. The choices were not left up to you. Along with several others, I was sent to the 1st. Battalion and assigned to the Queen's Company: More about this particular company later. My start at the battalion was not too encouraging, although I escaped unscathed. We were paraded in front of the adjutant, quite a high-ranking officer. As he was talking my gaze wandered outside of the office, looking through the window, country boy in the big city!! In no uncertain terms he brought my attention back to the matter at hand. He was not very encouraging when he suggested that agricultural workers, which I had been, usually finished up as cooks. Talk about stereotyping!! Fortunately for the Grenadier Guards I never did make it as a cook, never sent to try either. The Queen's Company was the elite of the elite, every man over 6"2", all very keen on spit and polish. While other companies had officers as Company Commanders, the Queen was ours, albeit in name only. She did apparently take an interest in the goings on of the company. She did not show up while I was a member. I was told I was to become a Bren gun carrier driver, and, along with Reg. Mann, another one not too keen on spit and polish all the time type, I was sent to back Pirbright. More on this episode later. I should report though, that while in the Queen's Company, and later with Support Company, I did do some `Public Duties'. Public Duties is simply a word for doing guard duty at Buckingham Palace, St. James' Palace, the Tower of London or the Bank of England. I did my duty at all but the Bank. Must be a message there somewhere!! To you kids all this about Public Duties means very little. Actually it did very little for the guardsman either. Let me explain. First it meant that you were tied up on the duties for two days. If the Queen was `at home' it meant two hours on guard and four hours off, and when you were not on duty you were confined to a separate guardroom at the location. Interestingly enough the `old soldier', the guardsman with the most seniority, did the least duty and ran a little canteen on the side. So I'm used to the alleged privileges of seniority. The duties started off with a parade, and when it was our turn it meant nearly everyone in the company was involved. You were paraded by detachments, inspected by an officer.

It is hard to describe how you did it, but you learned!! It was a rotten way to start guard duty by `losing your' name as they (humorously) called it, which happened if the officer found something wrong with your turnout. I did not lose my name once. `Losing your name' meant that, say for instance, you were marching and not holding your rifle correctly, the non commissioned officer in charge would say, "What's your name", you'd give it, and he would say, "You've lost it". If you were unfortunate, someone would place your name in the charge book and later, you would receive, after hearing, extra duties. Fortunately you really had to be noticed several times before they would `book you'. It was seemingly worse when they learned your name, then it would be, "Sergeant Tidridge, you're idle on parade, do this or that, or you will lose your name." After a while, as sergeants, we felt they, the person directing the parade, would call a name, whether that person was doing anything wrong or not. It just grabbed your attention and you automatically checked to see if you were doing things right.

The changing of the Guard and this applied, as I was to learn later, to changing the guard at any Guard's facility, meant the forming up of the new and old guards. Doing a little marching, getting on parade, a few arm (rifle) movements, and the officers handing over, and probably discussing the state of the facility, the new guard staying and the old guard leaving. If you missed seeing an officer, you could lose your name, again, sometimes. I guess now as I look back, the strangest sight would have been watching us 'get on parade' after ten o'clock at night. We had to carry out all the proper drill movements, lifting our feet off the ground, but making no noise when putting our feet back on the ground again. The NCO gave all his orders in a loud whisper, so that he would not wake the residents of the nearby homes. Ah! That's the Guards for you! While you were at the post you would be visited by the Duty Officer who would ask you questions about the regiment or any thing else he wanted to. Again, if you were not on the ball, you lost your name; you could also lose it every time you went on parade. And, any passing member of the public who felt you were not doing your job could report you for being idle on your post.

Guard duty at the Tower of London was different; you were there to guard the Crown Jewels and actually had a loaded rifle. You also had a fair amount of time off because there was limited duty during the day. At ten o'clock in the evening you took part in the Ceremony of the Keys. Again,a very well known ceremony watched by the public. As I remember it, the ceremony went as follows. On being approached by the Head Warden and his Party, the sentry on duty would come to the `on guard' position, which was rather ferocious, with the sentry facing the oncoming party with his rifle, with a fixed bayonet, and yelling: This was followed by another short ceremony, a prayer and hymn, and I think the playing of "Lights Out", by a drummer on a bugle. I can assure you guard duty at the Tower was a little different. The place is older than the hills, all kinds of ghost stories. Anne Boleyn who walks the Bloody Tower with her `ead tucked under her arm', is the most well known. It's dark, damp, dreary, and you can hear the water of the River Thames lapping against the walls, and of course, the older soldiers didn't make it any easier by relating their `terrifying' experiences while on guard duty. But hey, not many other have done it. We heard stories of guardsmen dressing up as ghost to scare the sentries. I'm not sure what my reaction would have been. I did have one small problem when I was on duty. People that you stopped were supposed to know the password, if they didn't know it there was bell in the sentry box that you rang and the sergeant would come running. Anywho, I'm doing my thing when this man and woman come towards me. I believe now the man was the worse for a night on the town. Anyhow, he didn't know the password, neither did his wife. It needed the sergeant to allow him on his way. St. James' Palace guard is not much to write home about, but again, not many have done it and now live in Canada. In retrospect, the whole guard system was a bit of a farce. I'm not sure we were actually guarding any of the places, particularly when you consider that a fellow was able to get over the walls of Buckingham Palace and get to the Queen's Bedroom. The Police didn't do a much better job either. LEARNING TO DRIVE

As you will recall I said that earlier I was then sent to Pirbright to learn to drive a Bren gun carrier, a Bren gun is a machine gun. A Bren gun carrier was a small tank that looked as though the top had been taken off. Not very big, not particularly safe, but at least I was taught to drive at the government's expense! Incidentally I never did see a Bren gun installed in a Bren gun carrier. We used ours to carry three-inch mortars. But that's the British army. The time at Pirbright was different, relaxed, no drill parades, and, as I said, we were being taught how to drive. I remember only a couple of incidents. If you stalled the motor you had to get out and insert a starting handle, some 5' long. It was inserted into the front of the vehicle and obviously went someway back into the vehicle. The sergeant would keep the motor turned off until you had cranked it several times. Then he would turn it on. Remember the dumb things they did to us in training, same principle. It worked. You really had to work at turning the crank, and the motor could cause the occasional kick back, and getting in and out of the seat was an exercise in itself. The vehicles seemed to be designed for people under 5'6", and the driver's seat for Mickey Mouse, however!! And, of course, if you screwed up while driving, the sergeant would turn off the motor, and out would come the crank handle. Another trick, to teach you to be able to start and move a vehicle off on a hill without it rolling back at all, the sergeant would find a hill, you got out and put your cigarettes under the rear track. You then had to start the vehicle, move off, without rolling back. To most of you this would sound strange, having mostly experienced automatic transmissions. However, by careful, skilled manipulation of the hand brake and clutch, you quickly learned how to do this tricky maneuver. The first sergeant we had was a friendly type, however, when we all went for our first driving test, conducted by an officer, this alone threw a scare into us, we all failed: A planned tactic, maybe? However, a tougher sergeant then arrived, he was the Sergeant of the Camp Police, bit of a twit. However, we all did pass the second time around. One other incident stands out, again this will be strange to you, but the gear stick was moved through the gears in a gate. This sergeant was demonstrating how easy it was to change gears. He insisted quite vehemently, that one could use one's little finger to change gears, and in a casual manner he tried to change gears. But it just didn't work. Finally, he had to resort to "ramming home" the gear stick. We had great fun repeating the episode to any one who had the time to listen. All mimed to perfection!! After the training we returned to the battalion waiting to be shipped to Berlin, Germany. 2020-04-10: Funny how you remember things! I just started a 'messenger' conversation with Colin Parker former 1st Battalion man c1954when a couple of bren carrier incidents came to mind! No connection with Colin. The battalion was on a scheme and along with three other carriers driven by myself, Reg Mann, Bert Baxter and Jack "Quick Draw' Mathewson we were heading quite slowly along a forest trail, It was muddy. Suddenly my carrier was dropping off the edge of the trail, . staying upright but sliding down the embankment. It came to a halt, no injuries. It was impossible, with the equipment to get the carrier back on track. At some point the RASC arrived with the right ruck, hauled me out and we were off,, goodness knows where! The driver and his mate were an enterprizing couple. We arrived at some barracks, they found a room and soon had a meal going on a heater of some kind. They left next morning and I needed a breakfast. I had no clean uniform of any kind, just some good old Bluebell for shining my Grenade. I'm almost at the canteen when I am confronted by a Corporal who tells me, in no uncertain terms, I am in no condition to enter the canteen. I leave hungry. All turned out OK allthough I have no memory of how I rejoined the battalion. The next incident could have been serious: Baxter, Mathewson and myself wer watching Reg Mann with a crew, come charging across some open ground...completely unaware the ground dropped off dramaticaly and his carrier came flying over the edge and landed, again upright. The rest of us thought it was pretty funny..we were just lucky. Berlin was our overseas posting. The Honour Guard was formed up in a court yard inside the Palace. I remember we arrived early, not unusual for us then or me now. We were allowed to "stroll" up and down the courtyard until the appointed hour. We were formed up, inspected, I think it must have been the Queen, and perhaps, only the front rank. Then we marched passed the Royal family, as they stood on a doorstep. Most of those around at the time were there, The Queen, Prince Philip, Margaret, and several other lesser lights. |

|

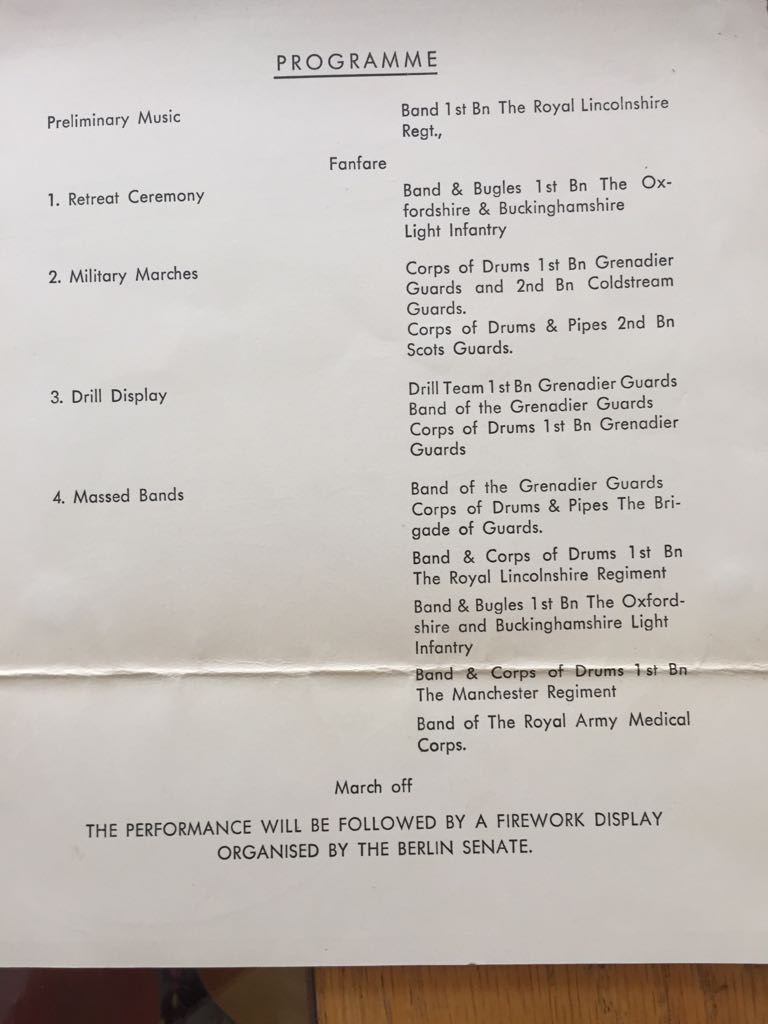

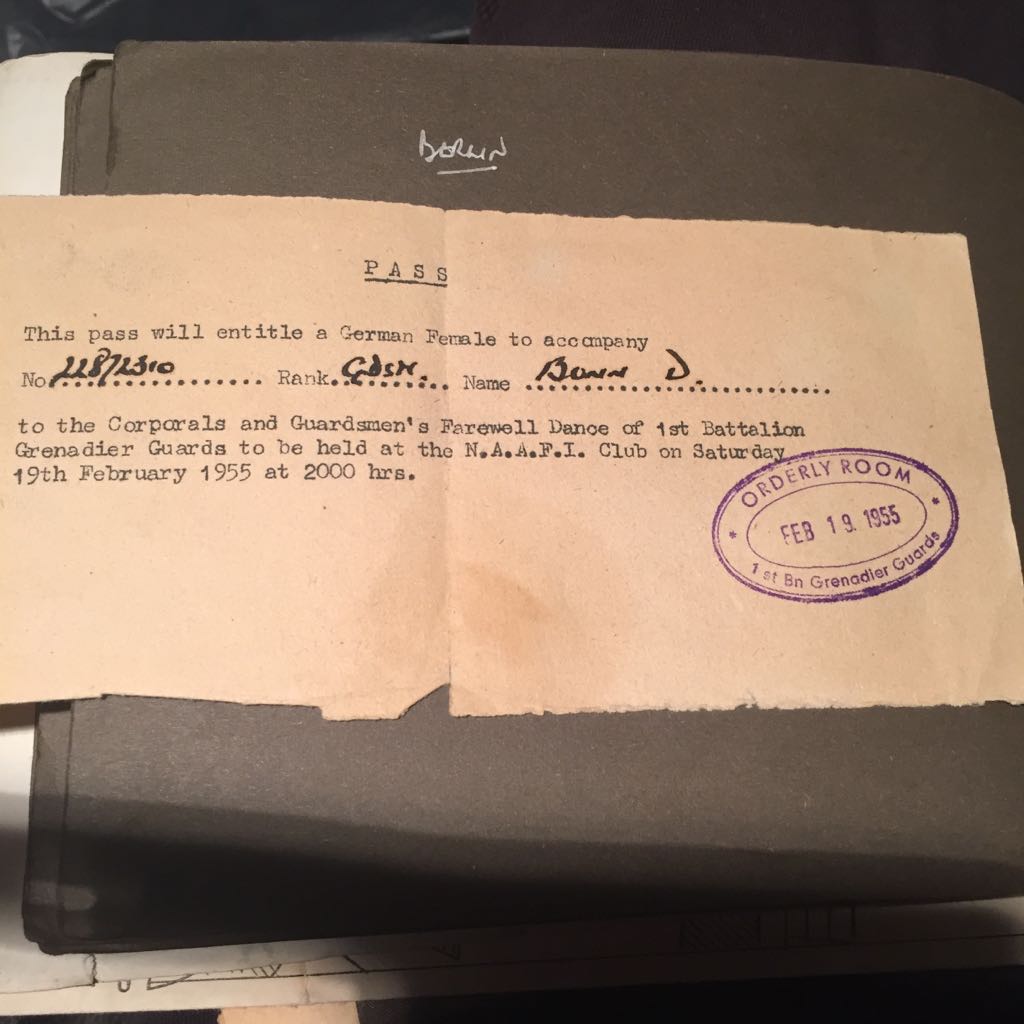

GERMANY BERLIN

According to writing on the back of the photograph of the ship to the left the battalion left Harwich for the Hook of Holland on February 11, 1954, at 11.00 a.m. arrived at 9.30 a.m. February 4, same year! Added is this terse comment, "Blimey, what a crossing." John Tidridge does not remember the trip. (On 'goggling the name of the ship it was discovered she was formerly the German minesweeper, Linz)

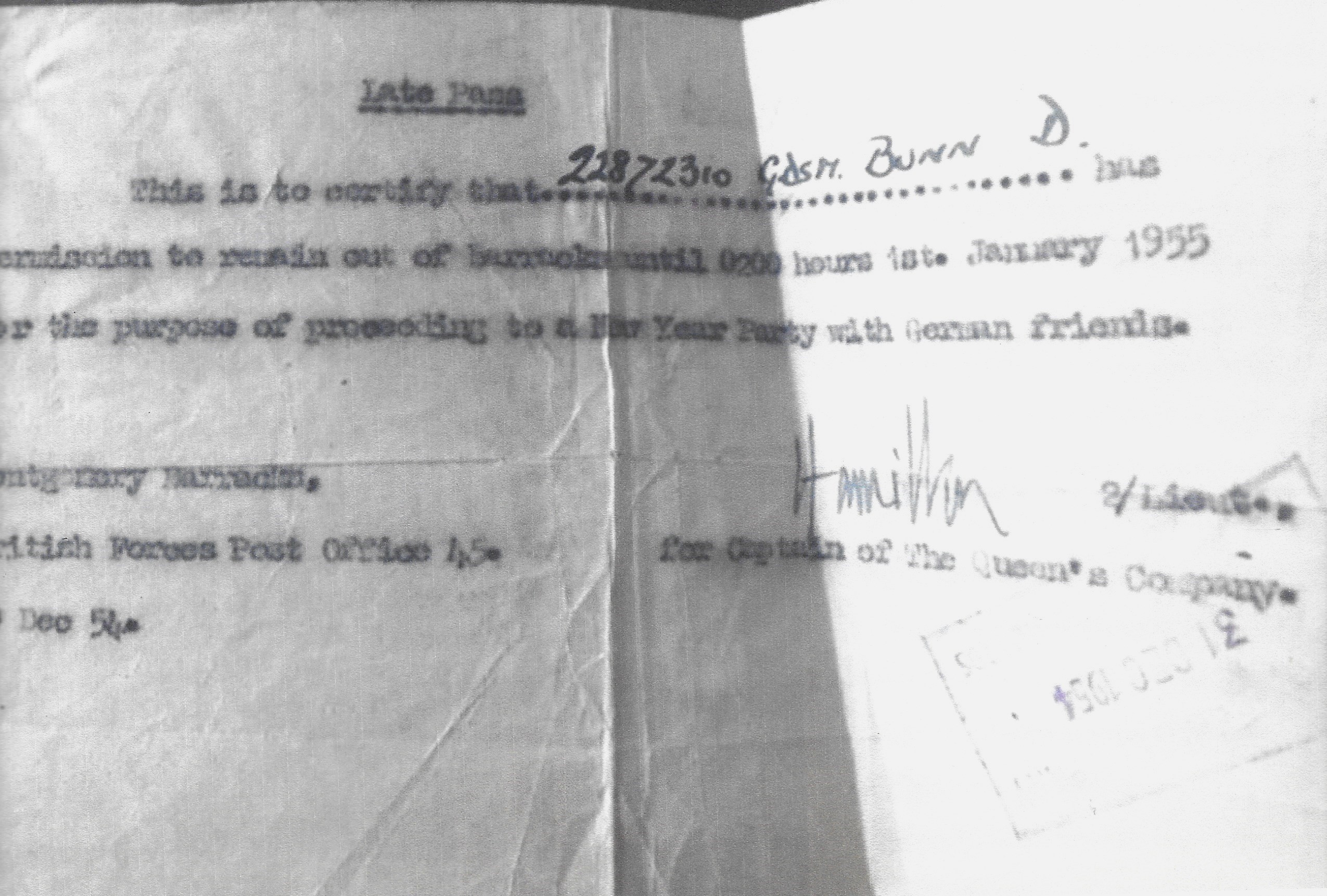

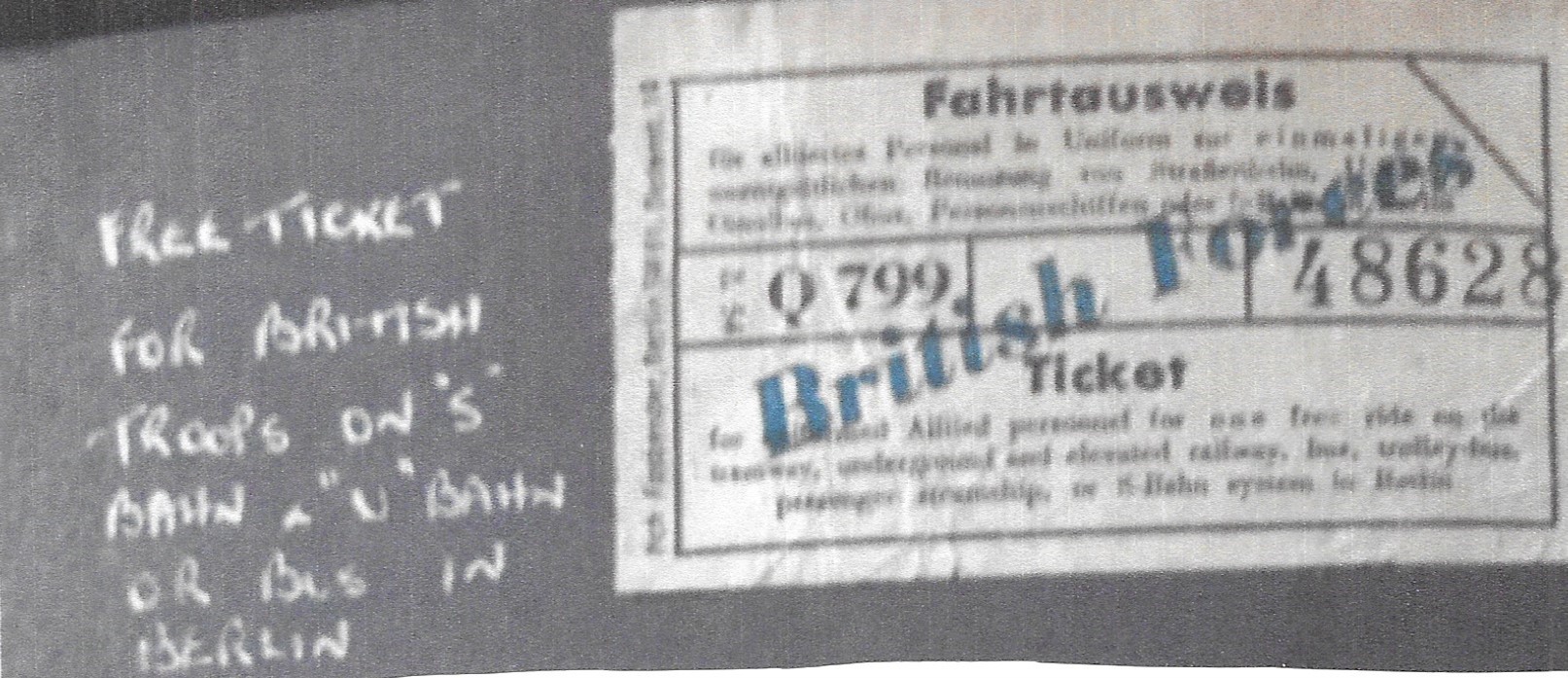

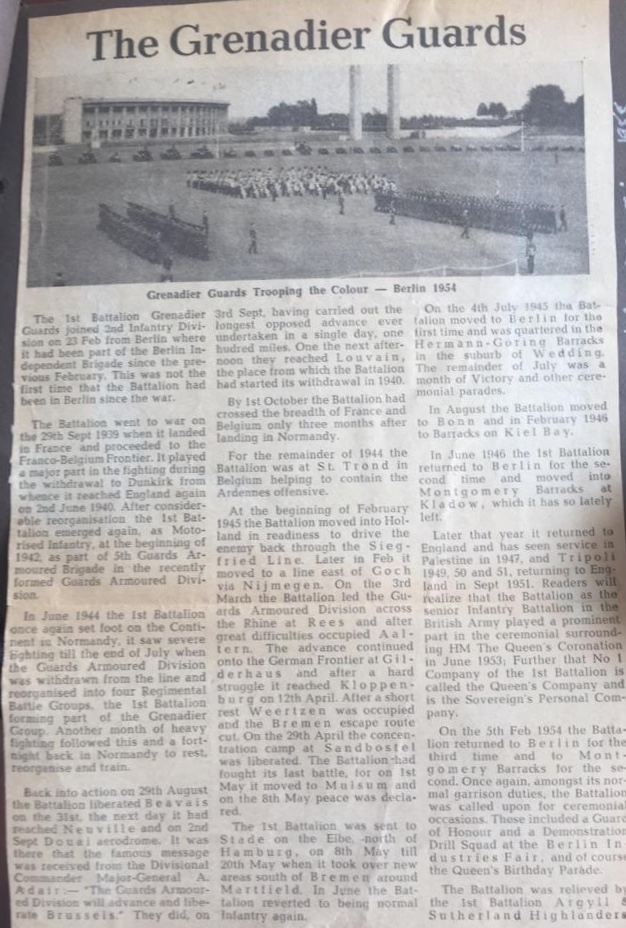

Shortly after that, the battalion moved to the British sector of Berlin and in to Montgomery Barracks. The Our barracks were on the edge of the Russian zone. One day the Russians held one of our units of about three men. They had apparently strayed into the Russian territory. They were released unharmed. Russia was not considered a friendly nation at that time. In fact, if you were charged with a minor offence, say, dirty boots, the charge would read, while on active service, etc.

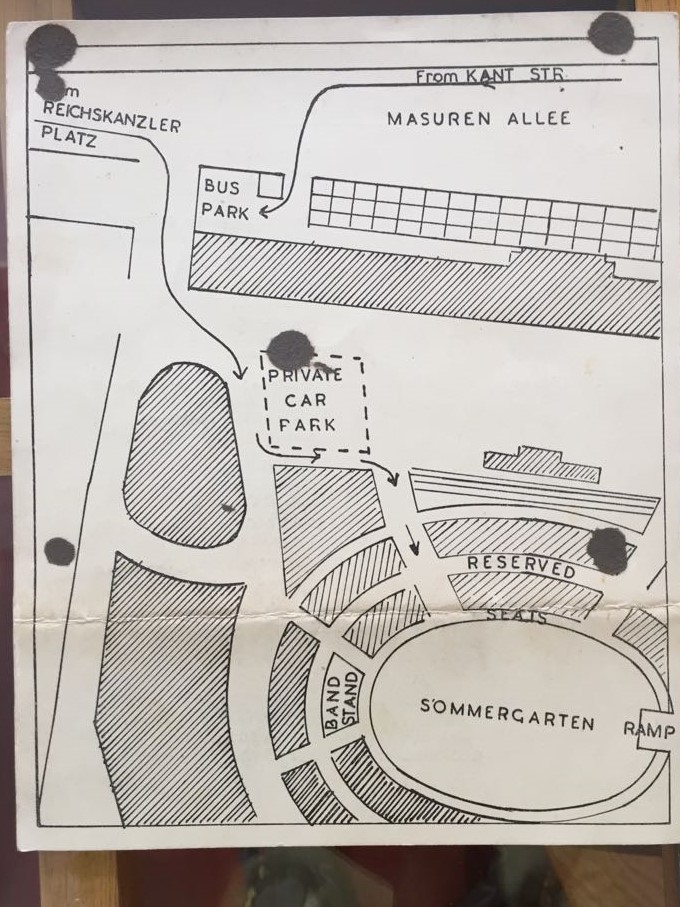

I visited the huge sports arena where Hitler made a lot of his speeches. I was in charge of a small group of men who had been detailed to help with an athletic event. Very easy and enjoyable. One of our duties was to carry out guard duty at Spandau Prison. Here the seven war criminals convicted at the Nuremberg trials were detained. They were the leaders of wartime Germany. They were all alive at the time. They did not lead much of a life, nor did they deserve to: Each month the Guard changed, one month it was the British, the next the Americans, then the French and then the Russians.

The prisoners lived at the same standard as the guards; apparently the Russian standard was terrible, followed by the French, then the British, and the best, the Americans. We also did joint parades with all the other nations. It was quite a unique experience. We also spent a lot of time fighting imaginary enemies. This was great fun and we all prepared to fight whoever that enemy might be, probably the Russians. Allegedly, though, we were all part of the Peace force for Europe. After year in Berlin we moved to Gort Barracks near Düsseldorf, and somewhere in between I had returned to England to be taught to be a driving instructor. This was great sport and made a real change. I was taught to drive a non-tracked vehicle, and to instruct others how to drive. The course passed very quickly, with only one incident that I recall. It was my turn to drive, we were in a three-ton vehicle, and the passenger door that I had to exit from was a considerable distance above the ground. As I tried to get out I missed my footing and I guess I just disappeared from the instructor's view, because, not only was the door high off the ground, there was a ditch parallel to the roadway. I landed in a ditch. The same basic skills of this fabulous performance have since been repeated on golf courses and in swivel chairs.

I conducted several driving courses with my pupils all passing. We actually drove a jeep called a Champ, five gears forward, and then by throwing a switch, five gears in reverse, plus four wheel drive. Powered by, get this, a Rolls Royce engine!! While driving a Roll's might have been great, however, whenever we went onto the Autobahn, we were the slowest vehicles on the road. Our vehicles were governed, so that about 72 mph was the top speed. There was no speed limit on the German highway. We experienced our first really slippery streets on one trip. We had (no not me!!) several minor tail-enders, and of course, being British, the accidents could not have been our fault. It was the road you know! Again we spent a lot of time training and dashing madly around the country. Much, I'm sure, the consternation of the German people, who did not treat us too badly considering we were an occupying force. One other little bit of information. We "Trooped the Colour" in Düsseldorf. There was a wide spread strike in England at the time and the Guards stationed there were doing the regular jobs to keep the country going. So, we had the honour of carrying out the parade in Germany. We had the R.A.F. Regiment and the Lincolnshire Light Infantry with us as part of the parade. The public was invited and I can tell you the Germans are an enthusiastic military minded lot. Every time we did a military movement they cheered and clapped. We were a pretty smart lot anyway, and it was great sport. They finally had to be told to wait until the end. The `Trooping of the Colour', I think, merely showed that the Regiment(s) were remaining faithful to the Monarch. Tradition don't you know. Oh, yes, I was not always the careful (slow?) driver I later I became. I nearly tipped my jeep over. I was driving it to a soccer match, not too far from the barracks. Was driving way, way too fast, and came to a corner that was sharp, and I mean sharp, I had to drive off the road, go into a farmer's field to finally bring the vehicle under control. I can assure you my passengers were not impressed. I also embarked on a criminal career during my time in the army. It happened this way: and all over ice cream. I was a sergeant and there were three other guardsmen in the jeep with me. We were part of a convoy of several hundred vehicles, we were moving very slowly and, in fact, as I recall, the whole move was punctuated by long stops. One of these stops was in a village. It was very hot and I thought it would be a good idea to stop and buy an ice cream. After all, how long could it take to buy four ice creams? However, I guess the guardsman who volunteered to go couldn't speak German, the storekeeper either couldn't speak English, or perhaps the money, in a single note, was too large for him to change. However, to cut a long story short, it took ages to get the ice cream. In the meantime the vehicles in front had moved off and here we were holding up large numbers of vehicles so that we could have an ice cream. An officer came by and I was told I was in open arrest. This simply meant I would be charged at some later date for holding up the convoy. I never was, but we never did get our ice cream: The hazards of war and all that kind of stuff.

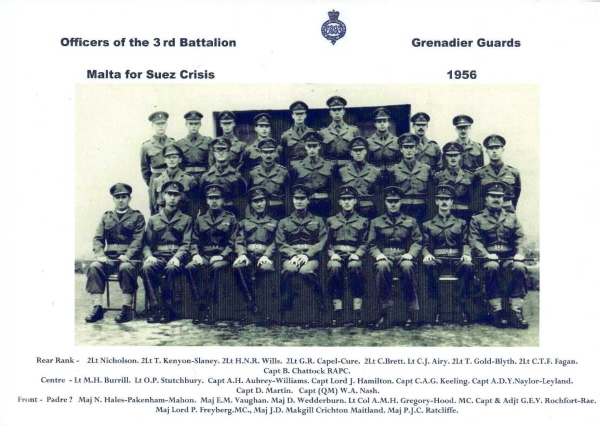

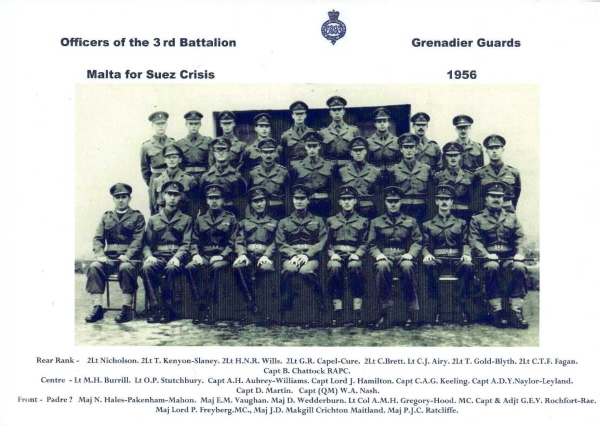

They took these exercises very seriously. Pretty soon my three years were up. I had started to correspond with a certain lady by then. But there was more to come. I'll probably tell you more about the period between my three years and my recall later. In the early part of 1956 there was a disagreement over who should control the Suez Canal: Which was and still is a very important water way in Egypt, in the Middle East. When hasn't there been trouble in the Middle East? The President of Egypt at that time, Nasser, took back the Canal. It depends, of course, on where you were born, on who took what, however, the French, Israelis and British decided it was their Canal. I think the French built it, the British had control of it and were under contract to hold it for several more years. The Israelis were afraid that if the Egyptians got control of the Canal they would use it to invade Israel. It all sounds so very familiar. All three felt that the control of it was absolutely essential to the well being of the free world. Anyway there was a series of threats and counter threats. I suppose someone drew a line in the sand and someone stepped over it. The Israelis, Arabs and French and the British were the most affected by this issue. |

|

THE SUEZ CRISIS

The Americans were opposed to any new war and Foster Dulles their Secretary of State was almost anti-British. How did this all affect me? As I think back on the positive results that came out of it, obviously the good Lord had things in mind for yours truly. I had not really settled down in civilian life. No, I didn't grow my hair long or hang about. I had a job, but things were not settled. There were rumours of war and it was said that several thousand experts would be recalled into the army. I assumed this would leave me out!! However HM Queen Elizabeth had other ideas and I received a telegram indicating that I was to report back to Pirbright, and be prepared to serve again. So that's what hundreds of us did. We quit our jobs and returned to the army. The jobs were to be kept for us, so off we went. We were very quickly issued our kit and uniforms. Then we were moved into Windsor (Victoria) Barracks, near London. Then about a week later we were shipped out to Malta, an island in the Mediterranean Sea. I suppose while we were all apprehensive, we never dreamed for a moment, though, there would be war or anything like that. We must have been dumb; why else would they have called us all back again? We made out our wills before we left England. Very shortly thereafter we were on a troopship leaving Southampton. The regimental band played us out of Southampton, that's right, our troopship left from my home town, with, `Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier", ringing in our ears. Frightfully British tune doncha know!! A bugler played part of the tune on a rifle, with the mouthpiece of a trumpet in the barrel of the rifle. We left Southampton in the New Australia. I don't remember much of the trip

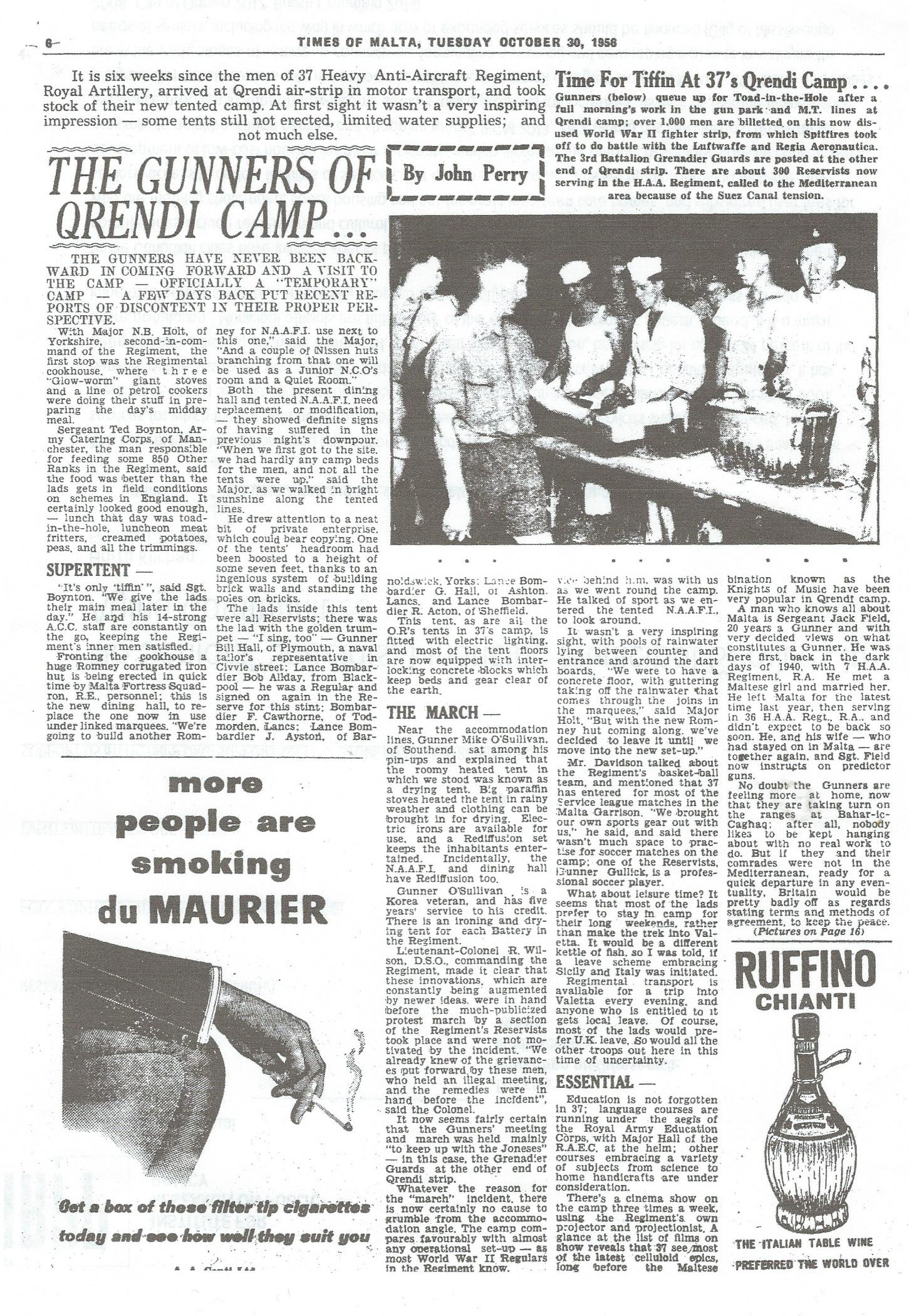

We were billeted in tents on an airfield, (Qrendi) by a village of the same name. A picture of the village church is to the left. There was no grass, but concrete. As sergeants we had beds, the guardsmen had straw mattresses. We had to do all kinds of things to ensure the rain wouldn't get in under the canvas. Malta was probably the place where I was made aware that we are responsible for our own actions, and that one should not put too much trust in others. I think it has had both positive and negative effects on my life ever since. It happened this way. We were ordered to prepare for a drill parade. In order to do this one had to shine one's boots to a high degree of shine. Several of us sergeants were discussing the merits of this type of garbage and as a crew we decided that we would simply not spit and polish our boots for the next day's parade. We left for our respective tents. Next day only one sergeant had followed through with this pledge, which I suppose, in effect, was mutiny of a kind. It was me. I got dinged for having dirty boots on parade. This resulted in some minor inconvenience at a later time. Sure taught me a lesson.

I was also 'arrested' in Malta, nothing serious, but in the army it was close to mutiny. Let me explain. I had played on our soccer team and had injured my feet. You should have seen the boots they gave us. This arial photograph shows the Qrendi Airfield ca1956. It came from Emanuel Muscat of Malta. I believe our regiment lived on the forward slash leg, but I am sure someone will correct me if I am wrong. Emanuel asked if anyone has any pictures of the Airfield would they consider emailing a copy to him at:

Anyway I was given, what they called, 'excused boots' this meant that I did not have to go on parade. After several days I reported to the medical officer and was given `medicine and duty', which, as the name implies, meant I was required to go on parades and all those good kinds of things. There was a drill parade that same morning. I chose not to go on it as did apparently dozens of others. However, I was lying on the bed in my tent when one of the senior non?commissioned officers did an inspection, found me, and told me to put myself in close arrest. This meant marching off to the guardroom (tent) telling the sergeant I was under close arrest and he `locked' me up in the corner of the tent. Actually I just sat on a chair waiting to be marched off in front of the Commanding Officer. This happened shortly thereafter. This additional story, all part of being in close arrest, probably won't mean anything to you; however, when you are in close arrest you are in fact a prisoner. In order to appear before the Commanding Officer another sergeant escorts you to the tent where the hearing is held. It was some considerable distance to the Commanding Officer's tent. A friend was my escort. We started off in grand style, on the double. We had to run about one mile. Halfway there we spot an officer, this required `breaking into quick time', regular marching. We managed this OK, but my escort was so out of breath he couldn't give the command to salute. So I did: Much to the officer's amazement. He was one of our own company officers, so he knew us. We finished the salute, broke into double time and dashed off, ignoring the officer's shout that we return. He never did do anything about it. I received a very minor punishment, but by now I am a hardened criminal.

On one of our schemes I almost caught an octopus; at least it almost swam into the mess can I was cleaning. (A mess can was an aluminium (aluminum here in North America)dish about 5" square and 2' deep). We were issued two such tins. They were used for eating, drinking and washing purposes. (hopefully not at the same time) If one was short of washing?up water one could `wash' them by putting sand in them and drying up the remaining contents and then throwing the residue away. They also had a dramatic affect on all foods that had grease in them. As soon as the greasy food, such as eggs, was placed in them, the food congealed as the tins were always cold. Should mention to, that I had started off in another company, not Support Company, which meant that I would have been marching all over the place, and I did for a while. Then I was transferred to the machine gun platoon that meant we rode everywhere. If I hadn't been transferred then I would have missed the following. We were on a scheme, fighting an imaginary enemy, and judging by the way the politicians were messing things up, it could have been anyone, including the Americans. We were ordered to return to our camp. The first thing they told us was that plans had changed and we were to board a minesweeper for exercises at sea. Aha!! Then we had a kit inspection. This is where every piece of equipment you have been issued with is checked to be sure it's all present, very strange. The trip across the Mediterranean was uneventful (if you call having everyone on board seasick, including the captain, uneventful) until we were just outside of Port Said (Egypt) harbour. Then we began to sweep for mines. We, the soldiers were told to stay out of the way; we did not need to be told twice. The sailors were quite happy because they received a bonus for every mine that was destroyed. We did not destroy any. I want to mention one little incident here and couple it with an incident that occurred when I was a kid, on the way to church. Together, while on the way to church, with a couple other guys, we came across the Fire Brigade, as we called them. They had their escape ladder up the side of a building. One of the firemen asked if I would like to go up the ladder. I declined. It was some 20?25 years later that I had to come down a similar ladder!! I had to help a young fellow down from the Calder water tower that had climbed to the top to attract attention about something or other. Now to the other incident: When we were on the minesweeper we drew alongside the supply ship. It was mail call. The other ship must have been over 60 yards away because of the rough sea. One of our sailor's shot a line to the ship, and rigged up, what I think it is called a Bosun's ladder. It's just a harness strung between the ships. A sailor merely seats himself into the harness and the sailors in the other ship pull him across the water. Again we were asked if we would like to try it, we, the soldiers all declined. I'm 59 years old now. I wonder when I will have to use one. Although the war was almost over before we arrived, aircraft were still sending rockets into the city as we entered the harbour. At this point the minesweeper ran aground on a ship that had been sunk by the Egyptians. We were never told how much damage had been inflicted on the ship. At any rate, we were taken off the ship and stationed in a Brooke Bond Tea factory. I don't remember too much about the tea factory except that when we went to go to the toilet there was nothing to sit on. The place was all nicely tiled,with a flushing system, but no seats. There was the tiled floor with a tiled hole. That was all. I suppose one would get used to it in time. Although I don't know for sure, it had, I beli Again my criminal background comes to the fore. To backtrack just a little: When we came across on the minesweeper, we sergeants ate in the Petty Officer's mess. We lived like kings. We thought we would return the favour by taking some tea to the ship. A staff sergeant and about four other sergeants and I loaded a large, large bag with tea and made for the harbour: To get from the shore to the ship raised a bit of a problem, quickly solved when we saw an unattended rowing boat. We all took an oar, except for the staff sergeant, who yelled out the time for stroking the oars. Military training rushing to the fore here, and we rowed across the harbour and presented the tea to the somewhat surprised sailors. I supposed we could have been court martialled. While in the tea factory about four of us were sent to guard a small village. We spent 18 hours watching this place, no food except for some very green grapefruit we were given by some passing soldiers. It was a long day. The day ended with a patrol coming to relieve us, and us being chastised for failing to identify the patrol before we allowed them up to our position. Ironically the patrol made so much noise we knew who they were long before they arrived. It was a good thing that we were all on the same side!! The official record shows that the Allies won the war, the Egyptians , however, still probably have their own victory parade. It seems that very shortly thereafter we were to return to Malta and we boarded another minesweeper and headed back to Valletta, Malta. On the way the minesweeper caught fire, burned out a motor and we were towed home. I have never been so glad to get off a boat in my life. We returned to a deserted camp. The rest of the battalion had been shipped to Cyprus. We obviously had to follow. The journey to Cyprus was made in a smaller craft. The journey was uneventful; apart from the fact that I ate my first real steak on board. The steak was rare, very rare, but was it ever good.