|

|

|

Arthur Charles TIDRIDGE (1883-1914)-Bertha May MERRITT [1883-1920]Marine, Regimental Number PO/11220

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

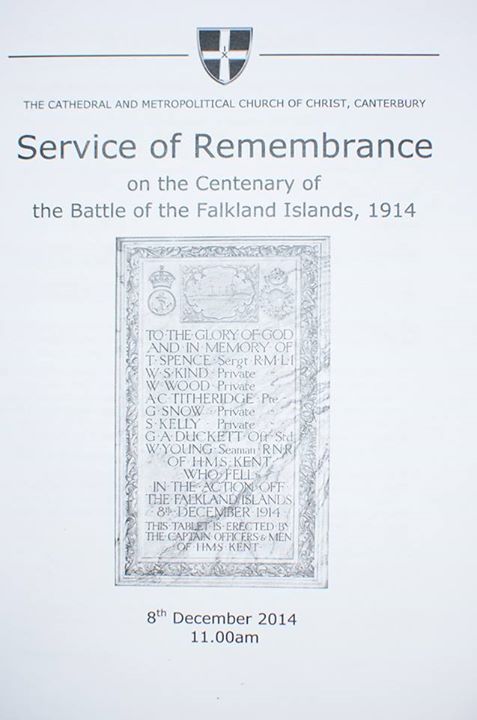

TITHERIDGE, Arthur Charles Private Royal Marine Light Infantry. Alfred enlisted in his regiment on January 5,1901, with register number 11220. Alfred was was killed near the Falkland Islands. His ship, the HMS Kent, was in conflict with the German ship, Nurnberg. On December 8, 1914, serving on HMS Kent was a gunlayer of the 6" gun in A3 casemate. He was very severely burned about the head, trunk and limbs. He was brought into sick bay where picric acid dressings were applied and morphia administered but he died of shock at 11.40 p.m. on December 8. The above info from Falklands battle:report on casualties, Catalogue reference:ADM 1/8405/459 I have found a memorial for this Titheridge in Canterbury Cathedral, England. There was around 10 other names on the memorial, although the account written by Captain J.D. Allen states that only 4 died and 12 were wounded. I can only presume that some died later. The memorial says that he was serving on HMS Kent and died in action off the Falkland Islands on the 8 th December 1914. The Memorial was provided by the Captain and crew of his ship. The Captain has written an account of the action on this day, but mentions none of the dead by name. Diary of Captain J. D. Allen, RN (HMS Kent) Quoted in Gallant Gentlemen by E. Keble Chatterton, London, 1931: No time was lost and at twenty minutes to nine, just under half an hour after the signal was received, the Kent was under way and steaming down the harbour past the flagship. A general signal had been made for all ships to raise steam for full speed. The flagship signalled to the Kent to proceed to the entrance to the harbour and wait there for further orders. From aloft we could now see over the land two cruisers approaching the harbour; one had four funnels and the other three funnels. We discovered later on that they were the German cruisers Gneisenau and Nürnberg. Meanwhile, all our ships were busy getting clear of the colliers, raising steam and preparing for action. In the Kent we had prepared for action coming down the harbour, throwing overboard all spare wood, wetting the decks, and clearing away the guns. We hoisted 3 ensigns including the silk ensign and Union Jack which had been presented to the Kent by the ladies of the County of Kent, and which we had promised to hoist if ever we went into action. The Gneisenau and Nürnberg came steadily on towards the harbour until they were only 14,000 yards from the Kent Suddenly we heard the Canopus open fire on them with her 12-inch guns across the land, and we saw the shell strike the water a few hundred yards short of the German ships. This must have surprised them, as Canopus was hidden behind the land. About this time also they must have caught sight of the tripod masts of the Invincible and Inflexible, as they immediately turned round and made off. We could now see the smoke of three more cruisers coming up from the southward: these were the Scharnhorst, Dresden, and Leipzig. The Glasgow was now coming down the harbour, and soon afterwards the Invincible and Inflexible came out, followed by the Cornwall and Canarvon The Admiral now signalled to the Kent to proceed and observe the enemy's movements, keeping out of range. Off we went at full speed ahead in the direction of the enemy's ships, which were now clearly in sight to the south east, hull down. Presently the Glasgow came along full speed and passed us, then out came the Invincible and Inflexible sending up great columns of black smoke, then the Canarvon and Cornwall. It was a magnificent sight. It was a glorious day just like a fine spring day in England, a smooth sea, a bright sun, a light breeze from the north-west. Right ahead of us we could see the masts, funnels and smoke of the five German cruisers, all in line abreast and steaming straight away from us. At 10.20 a.m. the signal was made for a general chase, and off we all went as hard as we could go. It was only a question of who could steam the fastest. The Invincible and Inflexible were increasing speed every minute, and soon passed the Kent. They were now steaming 25 knots and were rapidly gaining on the enemy. At 12.55, the Inflexible opened fire from her fore turret at the right hand ship of the enemy, a light cruiser (SMS Leipzig). A few minutes later the Invincible opened fire at the same ship. As the first shots were fired, the Kent's men cheered and clapped. They were as happy and cheerful as any men could be, and you might have thought they were watching a football match instead of going into action. The first shots fell short, as the nearest ship of the enemy was still out of range, but at 1.20 p.m. a 12-inch shell fell close alongside the rear ship and the three light cruisers the Nürnberg, Leipzig, and Dresden turned away to starboard to the south-west. Seeing this, the Kent, Glasgow, and Cornwall turned to starboard, too, in chase of them As a result of these movements the Kent was now steaming across the wake of the big ships, and about four miles away, so we had a splendid view of them without any risk of being hit. It was a wonderful sight, and the German ships were firing salvo after salvo with marvellous rapidity and control. Flash after flash travelled down their sides from head to stern, all their 6-inch and 8-inch guns firing every salvo. We could not see our own battle-cruisers so well, on account of their smoke, but it was evident they were keeping up a rapid fire. We could see their shell bursting all round and on board the German ships. The battle became one of separate engagements, with Invincible and Inflexible engaging Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. The fastest German ship, Dresden escaped; Cornwall and Glasgow engaged the Leipzig, leaving Kent to go after Nürnberg:

HMS Kent and SMS Nürnberg Kent Nürnberg

It was nearly four o'clock, and the Nürnberg was still some distance ahead. Should we be able to catch her before it was dark? Orders were sent to the engine room to make a supreme effort to increase speed, and splendidly the engineer officers and stokers responded. There was little we could do on deck, So we assisted the stokers by smashing up all the wood we could find, spare spars, ladders, lockers, hen-coops, targets, etc., into suitable-sized pieces, and passed them down to the boiler-rooms to put on the fires. We were going along at a tremendous speed now - 25 knots - and there could be no doubt that we were steadily gaining on the enemy. At 5 p.m. the Nürnberg opened fire with her after guns. It was a great relief when we saw the flash of her guns, for then indeed we knew that we were gaining, and we all felt quite confident that if only we could get within range of her we should soon sink her. It was exasperating to know that we must submit to being fired at without being able to hit back until we could get near enough for our guns to reach her. But it was only a matter of time and the Kent could easily put up with a few hits at such long range without being any the worse. It only made us feel more determined We had several shots through our rigging and funnels, and one on the upper deck aft, but no serious damage had been done yet, and nothing to reduce our speed. It was now raining, fine rain and mist, and the light was getting bad. We altered course slightly to port, and opened fire with the fore turret and the two foremost starboard casemates. Owing to the bad light and the rain it was very hard to see the fall of our shot, but as far as we could see they were going very close to her. One of Kent's shells hit the Nürnberg's after steering compartment, below the waterline, and at about 5.35 p.m., two of her boilers burst, and her speed fell to 19 knots. The range was now closing fast, and at 5.45 p.m. the Nürnberg turned She had evidently given up all hope of escape and meant to fight As the Nürnberg turned, she started firing all her port guns. The Kent turned to port too, but not quite as much, so as to get still closer, and opened fire with the starboard guns as soon as they would bear. Both ships were now firing away as fast as they could, and getting closer and closer. The Kent was steaming much faster than the Nürnberg now. It was now 6 o'clock. The range was down to 4000 yards. Both ships were using independent firing, and firing as fast as the guns could be loaded and fired. The Kent was firing lyddite shell. We could see our shell bursting all over the Nürnberg, and we could see that she was on fire. There was a tremendous noise, guns firing and shell bursting, with a continuous crash of broken glass, splinters flying, things falling down, etc. It was hard to understand how the Nürnberg could survive it so long. At times she was completely obscured by smoke, and we thought she must have sunk; but as soon as the smoke cleared away, there she was, looking much the same as ever and still firing her guns. She now turned away from us, as if unable to face such a heavy fire. Her fore topmast was shot away, her funnels riddled with holes, her speed reduced, and only two of her port guns were firing. At 6.10 she turned towards us, steaming very slowly, and we crossed her bow, raking her with all our starboard guns as she came end on. Two of our 6-inch shells burst together on her forecastle, destroying her forecastle guns. After crossing her bow, we turned to port till we were nearly on parallel courses again, firing at her with all the port guns. This was a great joy to the crews of our port broadside guns, as up till now they had not had a chance to fire. It was the port guns' turn now, and well they availed themselves of the chance, simply raining shells on the Nürnberg. At last, at 6.36, the Nürnberg ceased firing and immediately we ceased firing too. There was the Nürnberg about 5000 yards away, stopped, and burning gloriously. We steamed slowly towards her, taking care to keep well before her beam, so that she could not hit us with a torpedo. As we got nearer to her we could see that her colours were still flying, and she shewed no signs of sinking. We had to sink her: there could be doubt about that, so at 6.45 we opened fire again. After five minutes, during which time she was repeatedly struck, she hauled down her colours. We immediately ceased firing. We could see now that she was sinking. Orders were given to get the boats ready for lowering, but (they) were riddled with holes. The men had now left their action stations and were all on the upper deck watching the Nürnberg. Ropes' ends, heaving lines, life buoys and life belts were got ready to save life. We could now see some of the men leaving the Nürnberg, jumping into the sea and swimming towards the Kent. At 7.26 she heeled right over onto her starboard side, lay there for a few seconds, then slowly turned over and quietly disappeared under the water. Just before she turned over we saw a group of men on her quarterdeck waving a German ensign attached to a staff. As soon as she had gone, we steamed slowly ahead towards the spot where she had gone down, so as to try and pick up as many men as we could from the ship while the boats were being patched. The sea was covered with bits of wreckage, oars, hammocks, chairs, etc., and a considerable number of men holding onto them or swimming in the sea. It was a ghastly sight. There was so little that we could do. Our sailors were shouting to them, trying to encourage them, telling them to hang on, etc Only twelve men were picked up altogether, and out of these only seven survived A north-west wind had sprung up during the afternoon, the surface of the sea was rough, and the water very cold. Now did most of us hear for the first time of our own casualties. In a large ship engaged in an action most of the men are fully absorbed by their own particular duties, and know little of what is going on in other parts of the ship until the action is over. We got back to the Falkland Islands the next afternoon, December 9th, and as we approached the harbour we met the Macedonia coming out to look for the Kent. We immediately signalled (through) her to the Admiral: 'Sunk Nürnberg. Regret to report 4 men killed and 12 wounded. Picked up 7 survivors. Wireless telegraphy apparatus is damaged'. All of Von Spee's squadron, with the exception of Dresden, had been sunk, together with two colliers. In no other naval engagement of the Great War was there such a satisfying and decisive victory for the British. It more than made up for the defeat off Coronel, and the Grand Fleet in the North Sea was not able to repeat the South Atlantic success. On 15th December, HMS Kent left Port Stanley to search for the Dresden, and together with HMS Glasgow, was present when she was scuttled at Juan Fernandez on March 14th, 1915. I hope you find this information interesting, I found most of it on the internet after I came across the memorial in Canterbury Cathedral. I was lucky to find it, as I was visiting the Cathedral to watch my Daughter Tiffany playing her recorder in her School Carol service, and theseat I sat in was just in front of it. From Jim Titheridge, e-mail address jim.titheridge@gmail.com |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

HMS GLASGOW |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

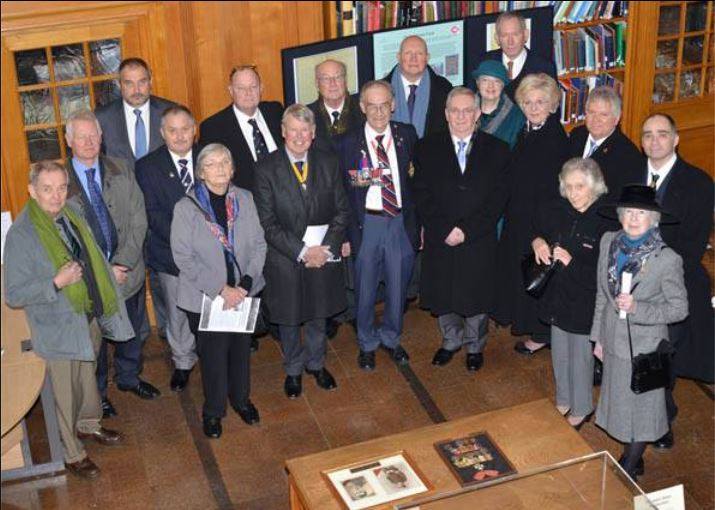

| Captains and former captains of HMS Kent | Some of the attendees at the Memorial Service | The bell from HMS Kent |

|

|

|

| For more details of the service click here | Pictures supplied by Jim. Titheridge | |

Sons of Arthur CharlesTFlock House was an agricultural and farm training school situated 14 kilometers outside of Bulls in the Rangitikei district of New Zealand. It was in operation from 1924 until 1987. From 1924 to 1937 sons of British seamen who had been killed or wounded during World War 1 were brought to Flock House. Here they were trained at the school and then placed on farms in New Zealand to start a new life. The scheme was proposed so that sheep farmers in New Zealand could acknowledge the debt they owed to the British Navy, who had kept shipping lanes open during the war enabling New Zealand farmers to ship wool to England. Between 1924 and 1937 over 600 seamen’s dependents were taken to this new life in New Zealand. Boys (and later girls) were selected by an advisory committee in London. Those selected were offered free passage to New Zealand, clothing and pocket money for six months and six months training at Flock House. At Flock House they were offered a range of skills with aim of them eventually becoming farmers.

Among these Flock House Boys were two of the sons of Arthur Charles Titheridge (from the last post). We believe that by 1918 these two boys were orphans. Their mother Bertha remarried in 1917 but died a year later in 1918.

The first child to be selected for Flock House was Albert Edward Titheridge born to Arthur and Bertha in 1910 in Alverstoke. At the age of 16 records show him to be a passenger in the 7th draft of boys and he sailed from Southampton on the Rotorua in 1926 to Wellington New Zealand.

Two years later he was followed by his brother Kenneth Edwin born in 1912 in Alverstoke. At the age of 15 he was a passenger on the Rotorua and one of the 12th draft of Flock House boys. He set sail from Southampton to Wellington on 20th January 1928 for a voyage lasting 42 days. His address is given as Shedfield Convalescent Home, Botley.

We know both boys settled into life in New Zealand but only have sketchy details of what happened to them. Albert is known to have married twice and had seven children and Kenneth also married and had children. Did they keep in touch with their family back in England? that we do not know. Perhaps some of our New Zealand cousins can fill in some of the gaps of what happened to these two brothers.

|

|

|

e-mail : John Tidridge

|

|

|